Original pages from English Dance & Song, June 1948

Original page from English Dance & Song, July 1949

The text from the images above is available here.

Back to Dance Index

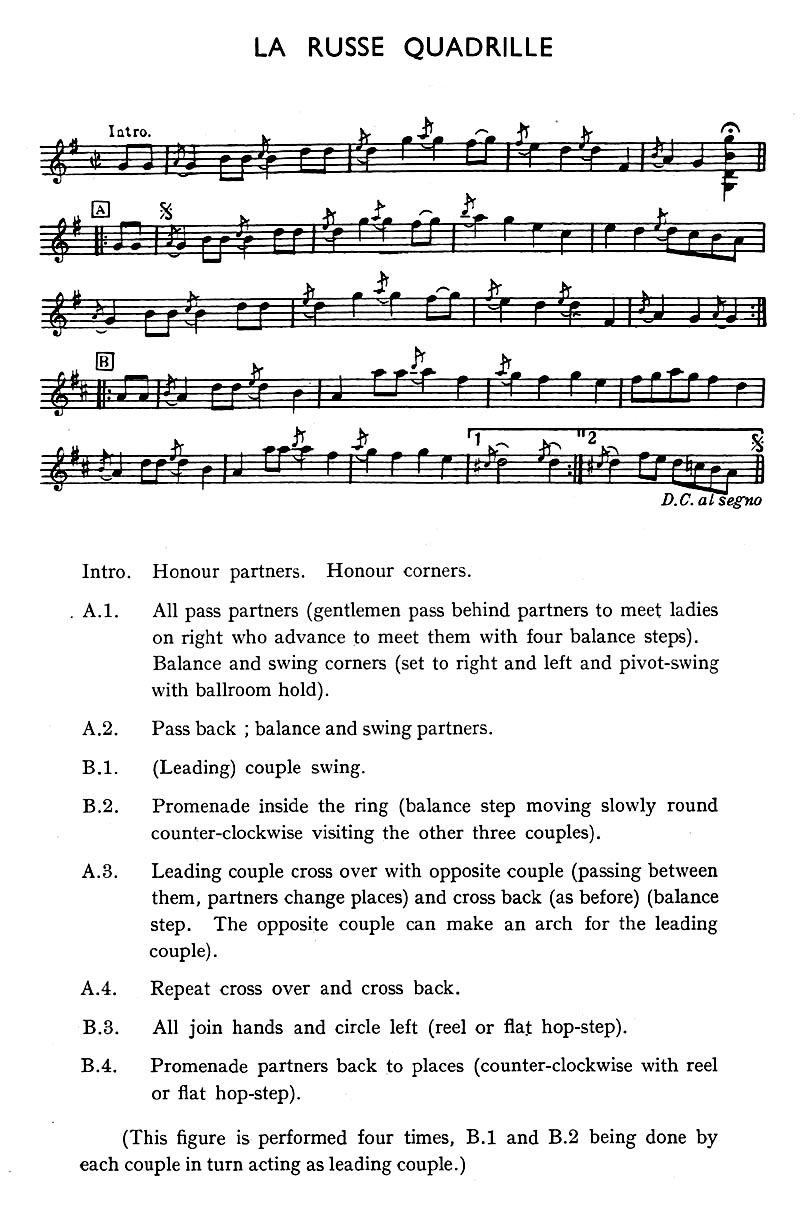

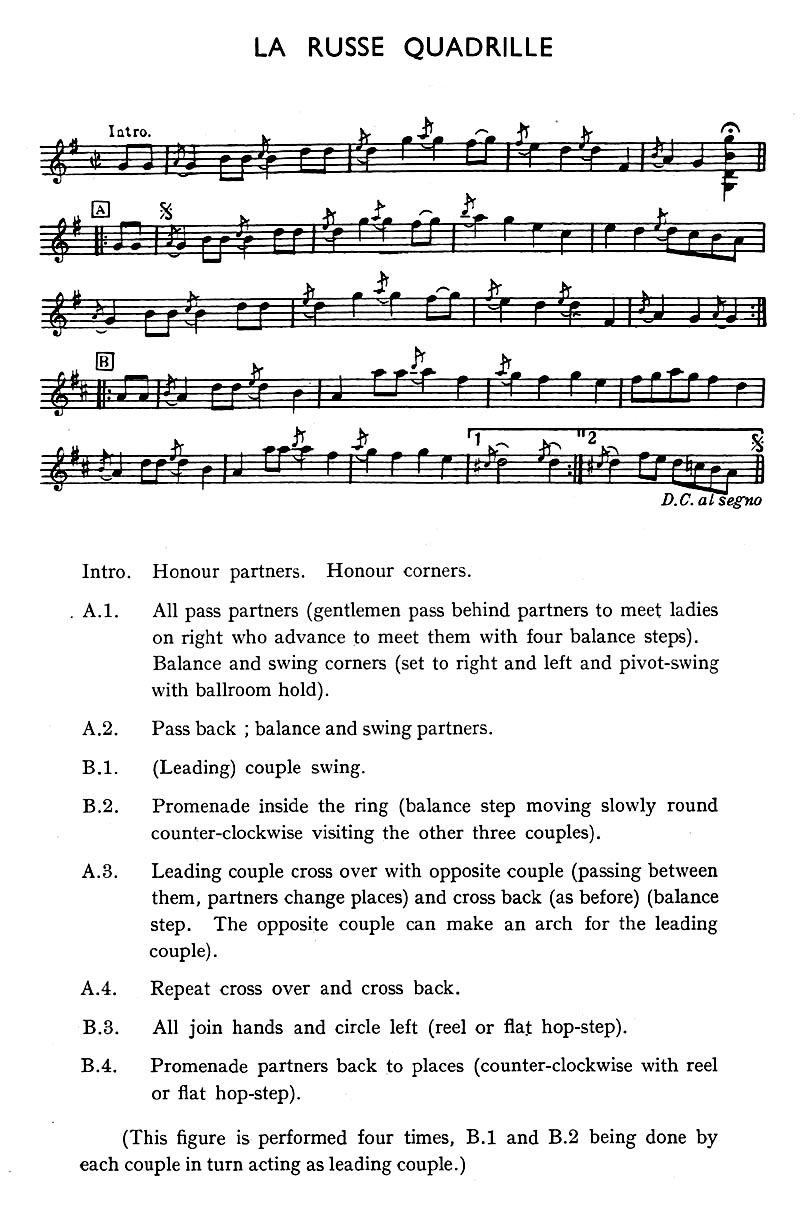

| A1 | Pass your Partner by the Left Shoulder (4); Set to the one you meet (4); Swing (8) |

| A2 | Pass your Partner by the Right Shoulder (4); Set to your Partner (4); Partner Swing (8) |

| B1 | #1s keep Swinging (16) (second time through #2s, etc.) - time to show your skills! |

| B2 | #1s Promenade AC inside the Set visiting the other couples then returning Home (16) |

| A3 | #1s & #3s: Cross Over, #1s between #3s (8); Cross Back; #3s between #1s(8) |

| A4 | Repeat |

| B3 | All Eight: Circle Left (16) |

| B4 | Promenade Home (16) |

I'd love to hear from you if you know anything more about this dance, its composer, its style, or its history.

Feedback is very welcome on any aspect of these dances or Web pages.

Please contact John Sweeney with your comments.